About one year ago Paola Donati, the artistic director of Fondazione Teatro Due in Parma (Italy), and I started to think about the value and meaning of the practice we call participatory theatre, which has become common all over Europe in the last 15 years.

Beyond the many definitions that try to frame this genre in a historical-theatrical vision (social theatre, social theatre of art, theatre of frailties…), what immediately struck us is its dual nature, which brings opportunities and risks. Also, in my experiences with participatory theatre and my work as a theatre educator with non-professionals, I have often had the chance to verify, on the one hand, theatre’s tendency towards social politics regarding the weaker parts of society (such as refugees or disabled people), and, on the other, an opposing tendency towards exploiting the non-professional actor as the new paradigm of contemporary theatre.

"Everything started in a void, an absence. By observing a lack of bridges [...] between those who are starting out on their life path and those who keep the secrets and memories of it."

The border which we are navigating – the one that separates professional and non-professional actors, theatre and polis, artistic research and political necessity – questions not only the function of theatre in today’s world, but calls above all for an evaluation of the competences and needs that inhabit our times, our cities and our theatres.

This is the basis on which Così vicino. Così lontano was born. It was the first step of a multi-phase project that aims to connect different parts and different ages of the city. Everything started in a void, an absence. By observing a lack of bridges—or relationships—between those who are starting out on their life path and those who keep the secrets and memories of it. The elderly and children. Opposite and complementary poles of a never-ending circle.

The engine driving forward the research on these two realities has been a group of 40 university students who started a lab where they could meet with seven children once every two weeks, have them play theatre and ask them questions about their lives.

As a first step, we went in small groups of students and kids to day centres for the elderly, nursing homes, ballrooms and different organisations in the city. As a second step, we asked the elderly men and women of the city to come to the theatre with us. We could call it a narrative barter: a way of having people experience different places in the city.

This first research phase was central to connecting the actors involved in the project—kids, students and the elderly—and to creating a new map of the city, a map made of subtle relationships, like in Invisible Cities by Italo Calvino. In this way, the theatre became an active catalyst in people’s lives, mixing gazes and points of view, ideas, stories and utopias. But how were we going to transform the many meetings, the stories we gathered, the perspectives, the entire process, into a theatrical form?

For this first study, we started with The Hour We Knew Nothing of Each Other, a play by Peter Handke in which the actors have no lines, only stage directions. A script of more than fifty pages describes the (extra)ordinary life of a square in a random city in the world. People passing by, laughing, running; men, women, children; greetings, half-stories, faces; imaginary loves, extra-slow movements, prayers; life that runs and flows. This daily flow, which often gives way to dreams and surreal realities, contains the possibility of the encounter: among children (with their way of inhabiting space, both onstage and in real life), the elderly (with their way of observing and telling) and the students (with their thirst for knowledge and their confusion).

An encounter halfway between reality and fiction, between the city and the theatre (as if it were possible to draw real borders between the two).

Many stories, no story?

Maybe.

The sole presence of these bodies that are so different one from another seems to show what spoken word hides letting you discover that everything you are looking for is already there, so near and so far at the same time.

The project, which will continue with a much more complex second step in order to deepen what we just unveiled, made plain a truth that is both ancient and contemporary, necessary in every study today: the need to transform spaces into communal places. Peter Brook’s ‘empty space’ of theatre can be the only one to remind us of this.

Reminiscing the feeling of the first step of Così vicino. Così lontano, I have to think of the ancient Chinese clocks, or hsiang yin, which indicated the passing of time with incense burning and consuming itself. And I think that every time I look for the feeling of things and I try to hold it, it has already gone, and what is left is the contrail of presence that smells of eternity.

Author

Vincenzo Picone

Stage Director, Fondazione Teatro Due Parma/Italy

Picone specialised in Theatre Disciplines in Palermo and Bologna. Part of his theatrical activity focuses on theatrical training projects, aimed at the new generations, collaborating with the company of Teatro dell’Argine, Fondazione Teatro Due in Parma and Fondazione Emilia Romagna Teatro.

This article was published in the ETC Casebook Participatory Theatre – A Casebook in Spring 2020.

Read all published articles of Participatory Theatre – A Casebook here

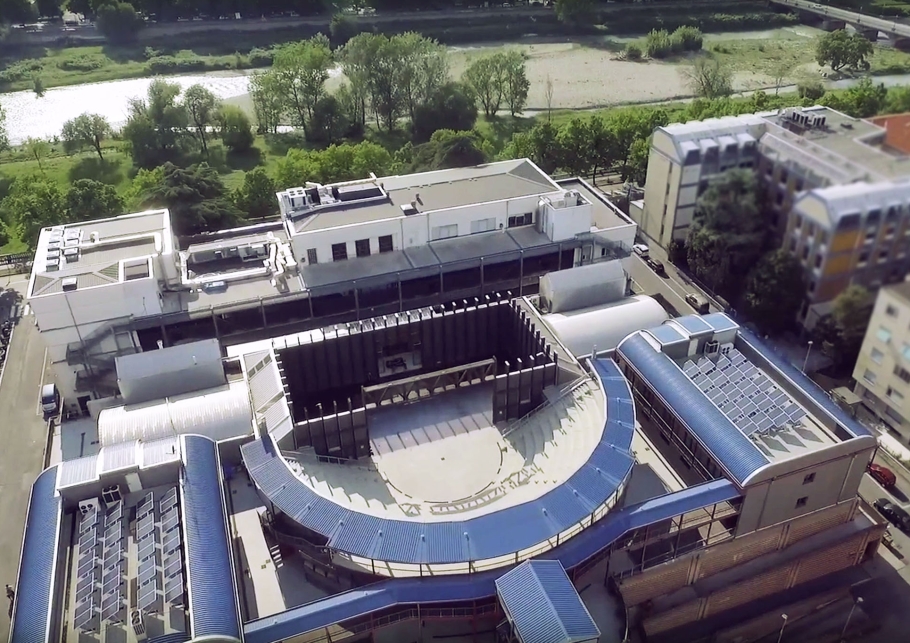

Top photo: © Fonzatione Teatro Due