Iris Laufenberg is ETC Vice-President and General Manager & Artistic Director of Schauspielhaus Graz, Austria. In this poetic analysis of the pandemic, she weaves together references to 20th Century German playwright Heiner Müller and a vampiric Tilda Swinton to set out how theatre (and art in general) influence our understanding of the world – and why we now have a chance to re-write this narrative into one that is more in tune with nature, death, and each other.

It is high time – right now, and even more so in times of a pandemic – to hold up a mirror to the world so it can get a better look, through the numbers of Covid cases and deaths, through the numbers of economic performance and forecasts, at its true face and circumstances. This mirror is and has always been art. In theatre, film and literature, death’s ugly face is given fine features in which we can all recognise ourselves, in order to learn at both the individual and the collective level. Without insight, there can be no awareness; without awareness, there can be no change, and that instead leads to paralysis, to being doomed to repeat the same thing over and over again. So let’s take a look in the mirror:

In my own life, the year 2020 ended with the death of a close relative. He made it to an advanced age and died of ‘natural causes’. So my new year began with a funeral.

This year was supposed to mark a change from the last: we were supposed to leave 2020 behind, with all its case numbers and deaths, and move forwards. Alas, things didn’t work out as expected. Not just for me personally, but for everybody: we are all still carrying the baggage of illness and death around with us in our everyday life.

Actually, we humans know that there is no life without death. As Robert Pfaller says: ‘We shouldn’t fear death, but a bad life’ (i). And whenever and however we cross paths with death, it is always an unexpectedly new experience. A test of endurance, to be sure: it has been at the centre of our lives for the entire past year. There was not a single piece of news that failed to induce fear or remind us of our own individual responsibility. Although this fear was present, it was exclusively aligned with abstract data: there were case numbers and faceless fatalities.

In art, and even more so in theatre, death often is and has been – from antiquity to the present – the centre of the action, even the protagonist. Theatre is a place of lies, intrigue, deceit; centre of tragic love stories that culminate in death and murder. The tragedies on stage give us an opportunity to work through things we’ve experienced or that aren’t settled in our own life, or to stand up to the powers that be. Because there is something that can be achieved on stage, in film and in literature, which, outside of the arts, might only be possible through spirituality: we are endowed with the ability to talk to the dead, a fact that playwright Heiner Müller emphasised throughout his life: “One function of drama is the invocation of the dead—the dialogue with the dead must not come to an end until they hand over the part of the future was buried with them.” (ii)

The combination of death and viruses has been a defining feature of art for centuries. Take the outbreak of the Black Death in Florence in 1348, which inspired Giovanni Boccaccio’s Il Decamerone. The central theme of this work is what we have been missing during these months of abstractly ominous numbers flooding us without interruption. Boccaccio has ten different people, among them aristocrats, escape the threat of the epidemic by fleeing to the countryside. While there, they distract each other with stories, told with great relish by a different person every day. Voluntarily isolating themselves on a country estate, they are not only escaping the misery of death but also the tristesse of everyday life.

The plot is quite different in Albert Camus’ classic The Plague. After the government’s initial denial of the epidemic, as the rats are dying miserable deaths in the streets and doorways of the city of Oran, the city gates are ultimately closed to everyone. Nobody can enter or exit the city. The death rate spikes; there aren’t enough coffins for the dead; curfews are issued, hygiene measures adopted, remedies tested; a path out of the misery is sought.

Although the events resemble one another and we have been experiencing them for over a year – if not up close, then by way of the endless cycle of images and reports and our attempt to find distractions in the media – we remember very little of the plagues of our ancestors. Not much attention has been paid to the history of epidemics until now, so these images have not been able to embed themselves in the collective memory: ‘For a long time little was known about how doctors tried to prevent an outbreak of the Plague in European port cities in the twentieth century. There is no collective memory of pandemics’, writes Clara Hallner in the Tages-Anzeiger, a Swiss newspaper, and still: ‘The Plague ploughed through the world three times. The most recent time it cost millions of human lives – not only in Europe.’ (iii). This sort of look at cultural history shows that – in very different genres and works of art – pandemics and diseases are very much inscribed in collective memory. Art, as memory brought to life, can be used to provide an additional perspective alongside the dominating views of virologists and statisticians, to mediate and come up with ideas for coping with the situation and to offer a hope-inspiring narrative (that does not constantly stoke our fears).

If the epidemic in Il Decamerone is a nuisance the privileged can escape by going to the countryside, it becomes a fortress for the people who are trapped within it in Camus’ The Plague. In Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau’s 1922 film Nosferatu, it even travels on a phantom ship carrying a multitude of rats and a vampire to the small city of Wismar. Or let us recall the scene in which Klaus Kinski, in his role as Count Dracula in Werner Herzog’s film adaptation of the same story, disembarks the Transylvanian ship, led by the ghastly rodents that spread the plague. The vampire is the incarnation of the ‘virus’: like the virus, he brings death, but never dies (out) himself; rather, he slumbers in secret, only to break out at some point in the future, metaphorically depicted in Nosferatu’s giant shadow cast across the buildings of the city. The motif of the unredeemed, of the inability to die, pervades throughout all these scenes. We see a more contemporary version of it in a scene from Jim Jarmusch’s 2009 film Only Lovers Left Alive, where Tilda Swinton, in inimitable casualness in her role as a vampire bored by immortality, drives through the deserted Detroit with her likewise eternal lover. Living forever has got to be draining. That’s why the topos of the human fear of death, the fear of danger lurking in every corner, is also imbued with the deep-seated desire for redemption.

We find it in countless works throughout the history of art, as well as in Richard Wagner’s opera The Flying Dutchman, which is based on the legend of a Dutch captain: he placed himself above God and nature and is cursed for it, doomed to sail the seas of the world on his phantom ship till kingdom come – apparently without ever being able to dock at a harbour. But still, every seven years he has the chance to be redeemed by a human sacrifice…

All these undead continue to roam the earth, or at least our shared cultural history. The virus, draped in bat’s clothes or dressed as a vampire, mirrors and embodies a threat which we allow to frighten and terrify us as we shudder gratifyingly in our seat at the cinema or on our sofa at home. With the certainty of having projected our own fears onto celluloid or the stage, we can banish them and go to bed in the dark comforted by the certainty that tomorrow will bring a bright new morning. At least, we’d been able to do that until early last year, when a virus began affecting us in a very real and physical way: so here and now we are forced to take a closer look.

The fact that epidemics and pandemics have always really existed is an inconvenient historical truth which had apparently really collectively been repressed or forgotten by society. It wasn’t until I read Philip Roth’s Nemesis that I understood for the first time the scale of the catastrophe caused by polio: although about 10,000 people still contracted the disease in Germany in the 1960s and it was only stopped after all children were required take an oral vaccine, the traumatic magnitude of this disease was hardly ever brought up throughout my time at school or in my family and environment. Plagues like SARS and Ebola also used to feel quite far away. The threat of a novel virus spreading across our globalised world was severely underestimated; it was something unthinkable. Likewise the fact that we globetrotters could – time and again – be infected with a virus and bring it along with us, spreading it to all corners of the world in a very short time.

We had been warned – if we had only wanted to listen – for many years by scientists and progressive thinkers all over the world. Not to mention that we culture lovers and cineastes could also have opened our eyes back in 2011: Contagion by Steven Soderbergh was dubbed an ‘exciting thriller’ with a star-studded cast (with Gwyneth Paltrow, Matt Damon and others). But from today’s perspective it was much more: it documented the cycle of an epidemic; it was a crystal-clear, realistically portrayed warning to humanity that our planet, due to our treatment of other living beings and our dominance of nature for our survival, will no longer offer us any security in the future.

Now the pandemic is slowly taking on faces and a history, and becoming easier to place into our era than the plague was. If we had merely been ‘fans of extraordinarily crafted science fiction worlds’ from the start of the twentieth century until now, these works of art and their ‘fantasies’ (such as in the 2013 novel The Circle by Dave Eggers) now suddenly depict what our life has become today.

Since the dawn of industrialisation at the latest, societies oriented towards unlimited progress and growth have exposed themselves as destructive weapons against the basis of our existence. The apocalypse can no longer be relegated to history, projected onto art or preached away in worship: we human beings have crowned ourselves King of the Universe and in the process have failed to weigh the consequences or take appropriate measures. Vampires and bats are getting closer now, tumbling down from the silver screen. We had sensed it before. I remember the issue of the increasingly reckless destruction of the environment and the unsustainability of our way of living were already quite evident to me back in the 1980s. According to evolutionary theorist Lynn Margulis, this is due to ‘our strong feeling that we are different from all other lifeforms’ or, simply put, ‘megalomania’ (iv). As the saying goes: ‘Pride comes before a fall’. But even Oedipus had to be blinded before he could see the scope of the tragedy that he had caused.

If our current geological epoch can still be framed by the term Holocene, which stretches from more than 11,000 years ago to the present day, in the 1990s the playwright Heiner Müller made a point of describing an ‘infinite present’, thus bringing the contemplation of our future to a halt. At a conference at Haus der Kulturen der Welt in 2013 Frank M. Raddatz argued: ‘Our idea of nature is outdated. Human beings shape nature. That is the heart of the Anthropocene thesis, which heralds a paradigm shift not only in the natural sciences but also seeks new paths in culture, politics and everyday life.’ (v). And so humanity was identified as a dominant influential factor on biological, geological and atmospheric processes: the massive waste of resources, contamination of the environment and disastrous interventions in nature are all being accelerated due to the human drive for (economic) growth and by globalisation.

The current pandemic has made this rapid progress of globalisation and the interconnectedness resulting from it at all levels crystal clear: within just a few weeks, Covid was detected on every continent. Until then, we had hardly ever realised just how ‘short’ the distances across the globe had become. And so it is no wonder that the most frequent (and, from this perspective, actually rather naïve) question put to culture and artistic creation over the past ten months was: Aside from all the bad, what good will come out of the Covid pandemic for our society? What will we have learned?

Such complex processes and (world) events, which frequently elude the power of a person’s imagination, not only require reflection and concentration and ultimately a narrative: crucially, this narrative also needs to spread and be absorbed into collective memory.

In light of this paradigm shift, we must acknowledge that we, in the arts and in general, will have to look for new narratives about our existence in the future. Shouldn’t art be granted more relevance in society? And, given that it has long proven its relevance, shouldn’t it be seen as a valuable partner or even as a necessary ‘tool’?

As early as the 1970s, Heiner Müller prophetically gave us a first taste of it in his ‘Mission’: ‘The rebellion of the dead will be the war of landscapes, our weapons the forests, the mountains, the seas, the deserts of the world. I will become a forest, a mountain, a sea, a desert.

The epidemiological historian Malte Thießen paints a rather bleak picture in his lecture ‘How epidemics influence society’ (vi), though not without pointing out the opportunities we still have to make changes: he also attests to an unusual historical amnesia when it comes to our epidemiological past – from the Spanish flu to cholera and the black death to polio and HIV. So while these diseases are seismographs of the ruin of societies, they themselves are also social in that they are contagious: when one person falls ill, it becomes a problem for everybody. As a result, epidemics also harbour within them the possibility of social emancipation. Since it is a question of life and death, it is also about the fundamental principles of our society. And here is where politicians and virologists would be sure to benefit from support from the fields of sociology, linguistics, history, psychology, and certainly art and culture.

To conclude these thoughts, I want to leave you with the vision of a future utopia: we will manage – thanks to our societal, emancipatory, self-reliant and reflectionist power – to unite and stand up against the widespread practice of nation states outdoing one another, against the putting up of borders (including the ones in our heads), against the reinforcement of stereotypes and the search for ‘scapegoats’. We will open up new spaces for thought and action, and replace our fears with trust in global responsibility in order to jointly solve global problems.

Oh, and in this utopia we’re also finally going to let go of a well-known phenomenon of our cultural history: the woman’s role in this upside-down David-and-Goliath vision. The roles of the sacrificial beauties – whether in Nosferatu or The Flying Dutchman – who have always and forever redeemed the patriarchal status quo will have no place in this utopia. Neither the young Senta nor the beautiful Ellen will stand outside of the landscapes wrestling one another, or at least they will not sacrifice themselves to humanity. Yes, Agamemnon may wage war against the landscapes embroiled in dilemmas that cannot be solved, but in the war of the seas, Iphigenia will not be there; and, if she is, she will stand by Agamemnon’s side as an equal. Either way, daughters will no longer be sacrificed. Nor will the storms allow themselves to be graciously appeased by any human sacrifice at all. The Oresteia will have to be rewritten.

Iris Laufenberg, 05.03.2021

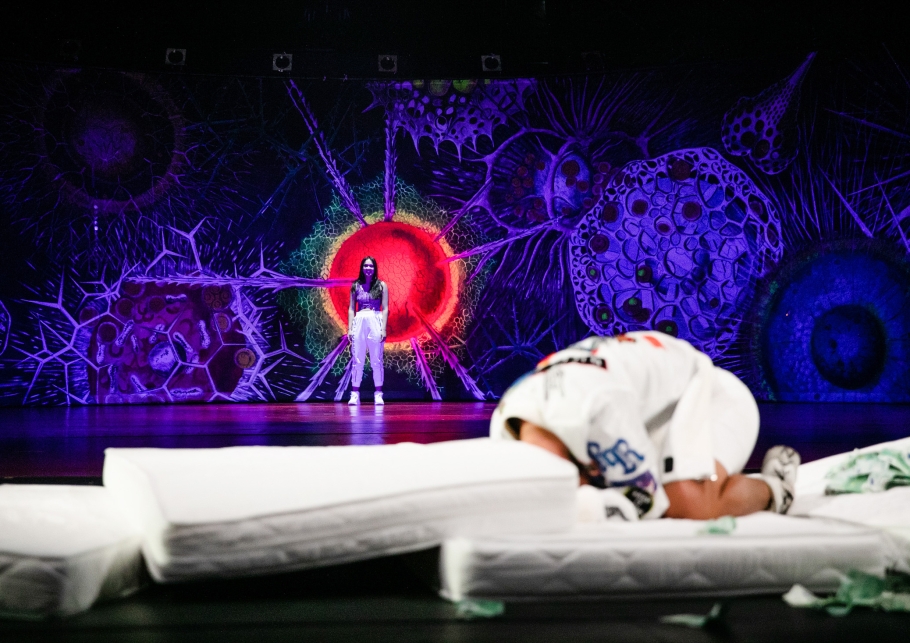

Images: Vernon Subutex by Lex Karelly, a production of Schauspielhaus Graz

The following texts and lecture are quoted in and served as the main inspirational sources for this essay:

Elisabeth Bronfen, Angesteckt. Zeitgemässes über Pandemie und Kultur, Basel 2020; Frank M. Raddatz, Bühne und Anthropozän. Dramatische Poesie der Zukunft – eine theaterästhetische Spekulation, in: Lettre International, no. 122, autumn 2018; Malte Thießen, Wie Epidemien Gesellschaft beeinflussen, 11.11.2020, Forum Paderborn, broadcast at the Deutschlandfunk Nova lecture theatre on 23.01.2021